What is my research about?

My research interests range very widely across politics, political economy and international relations. Empirically, most of my work has been focused on Southeast Asia and China, though in the past decade I have increasingly deployed analytical tools developed in that research to understand developments in the West, and these interests now combine in my most current work on the ‘New Cold War’ between the US and China.

At the heart of all my work is an abiding interest in the nature of the state and state power. It’s my contention that if you can understand the forces shaping state institutions and their operations, you can understand a great deal of what they do, try to do, fail to do, and so on, domestically and internationally. Gramscian state theory, as developed by Nicos Poulantzas and Bob Jessop, and the Gramscian ‘Murdoch School’ of political economy, developed at the Asia Research Centre at Murdoch University, Australia, have been my main inspirations. These approaches see states as expressions of political and social conflict, especially class dynamics, rooted in evolving political-economy contexts. With my longstanding collaborator Shahar Hameiri, I have developed these insights into an innovative ‘state transformation approach’, which centres contested transformations of statehood under globalisation, as a key analytical lens on domestic and international politics. Tracing outcomes to conflicts between social groups operating within and around the state allows us to understand why states behave as they do, and whose interests they ultimately serve, in a way that conventional International Relations theory cannot.

I have applied this analytical approach to a very wide range of topics, always revolving around questions of sovereignty, intervention and state transformation.

Southeast Asia, non-traditional security and sanctions

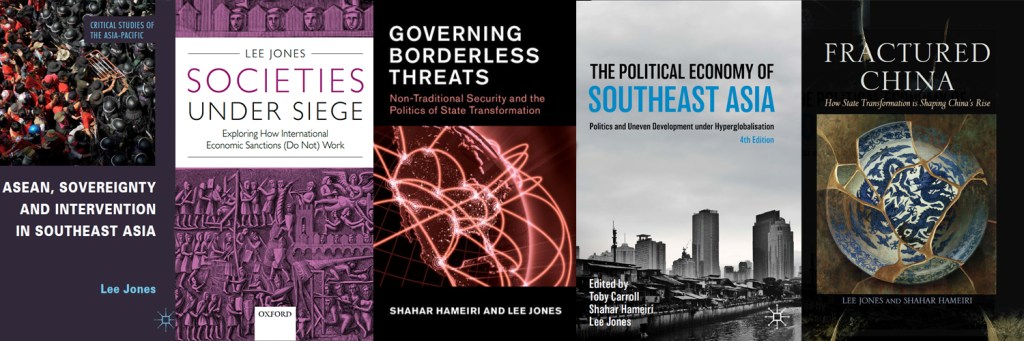

My early work, culminating in my first book, ASEAN, Sovereignty and Intervention in Southeast Asia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) explained why – contrary to governments’ own claims and the academic consensus – Southeast Asian states had, in fact, often intervened in each other’s internal affairs. I traced the development and violations of norms of sovereignty and non-interference to domestic dynamics of social conflict within these states, showing that they ultimately served the interests of ruling elites and the class forces they served.

In other work I have shown how the specific interests of social forces underpinning Southeast Asian regimes shapes the extent of their regional economic integration; the outcomes of international statebuilding missions in the region, particularly in Timor-Leste; and, more recently, the lopsided results of Southeast Asian states’ efforts to balance between rival geopolitical powers in the ‘New Cold War’. In 2020 I coedited the landmark fourth edition of The Political Economy of Southeast Asia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), which applies the ‘Murdoch School’ approach to a host of issues ranging from economic development to the environment.

With Shahar Hameiri, I applied this approach to understand how non-traditional security issues – threats like environmental degradation, transnational crime and pandemic disease – were governed, using Southeast Asian case studies, in work funded by the Australian Research Council. In our book Governing Borderless Threats (Cambridge University Press, 2015), we showed that NTS issues are primarily addressed today through efforts to transform states – to rescale and reconfigure governance so as to impose international agendas and disciplines on other parts of states and societies. However, socio-political conflict, rooted in the political economy of specific NTS threats, always shaped outcomes, often contrary to policymakers’ original intentions.

Around the same time I conducted an ESRC-funded project on international economic sanctions, inspired by my work on ASEAN’s unsuccessful interventions in Myanmar, during which I had noticed the failure, too, of Western economic sanctions. The result was Societies Under Siege: Exploring How International Economic Sanctions (Do Not) Work (Oxford University Press, 2015). The book developed a pathbreaking way to understand how sanctions work (or don’t work) by reconfiguring socio-political power relations within target states. Case studies of South Africa, Iraq and Myanmar demonstrated the power of the approach.

China’s rise

Shahar and I then turned our ‘state transformation approach’ to the central concern of the IR discipline at the time: the rise of China. Beginning in 2014, and eventually also funded by the Australian Research Council, we critiqued existing IR models of China as a unitary actor, showing that, in fact, uneven and contested dynamics of fragmentation, decentralisation and internationalisation were shaping China’s external relations. The outcomes of Chinese policy were less about a unified grand strategy hatched in Beijing and more about the specific political-economic relations clustered around specific Chinese state apparatuses, in interaction with their foreign counterparts. We again used Southeast Asian case studies, covering the South China Sea, non-traditional security cooperation (specifically around counter-narcotics), and development financing and the Belt and Road Initiative. Key publications from this work include Fractured China (Cambridge University Press, 2021), and a report for Chatham House which is one of the world’s most-cited discussions of China’s so-called ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ (a concept we thoroughly debunked).

Meanwhile, the weight of events pushed me towards researching my own society. In 2016, the UK voted to leave the European Union. As part of The Full Brexit, a network of academics, writers and activists, I deployed my analytical framework to the UK and the EU, tracing the way in which the UK state had been transformed by European integration, and the socio-political dysfunctions and conflicts arising from that. This work culminated in my coauthored book Taking Control: Sovereignty and Democracy After Brexit (Polity, 2023). The same tools, coupled with my past research on pandemic disease, allowed Shahar and I quickly to analyse the failures of Britain’s neoliberal regulatory state during the COVID-19 pandemic, notably in an award-winning article written in 2020 at the peak of the lockdowns, and subsequently the failure of the World Health Organisation.

The New Cold War

My current research, on the so-called New Cold War, also in collaboration with Shahar Hameiri, unifies my growing interest in the dysfunctional nature of Western states and politics – only deepened following a two-year secondment to the UK’s foreign ministry from 2022-24, where I advised policymakers on Southeast Asia and China – with my longstanding interest in China. Our project is a political economy analysis of the New Cold War. Our starting point is that the US (and its allies) has decided to pursue a Cold War-style conflict with China, replete with 20th-century geostrategic imaginaries of ‘blocs’ and ‘swing states’, in a context of 40 years of neoliberal globalisation which have ended meaningful ideological differences, shattered geopolitical blocs into transnational economic networks, and profoundly undermined the capacity of states to mobilise their societies towards publicly-desired ends.

The project, part-funded by another Australian Research Council grant, is guided by three key research questions: (1) Why have Western states decided to pursue this fight now? Put another way, what are the causes of this ‘New Cold War’ and what interests are being served by it? (2) How are efforts to compete with China unfolding, given the transformed nature of the US state and its political economy dynamics? We consider issues like global infrastructure financing; technological competition, particularly around semiconductors; and struggles over critical minerals. (3) How are third countries responding to this struggle, and why?

Early publications from this project include explanations of China’s approach to debt distress in the global south; the failures of Western efforts to compete with China on global infrastructure financing; the increasingly ‘miserly’ offer from both sides in global development; and a forthcoming special issue in Third World Quarterly on middle-ground countries’ ‘polyalignment’ strategies.

Research funding

Since 2010, I have secured nearly £1 million in external research funding. Key grants include:

- A UK Economic and Social Research Council award for the project on international economic sanctions (£127,557, 2010).

- Australian Research Council awards (with Shahar Hameiri) for research on non-traditional security (AU$305,000/ c.£192,000, 2010) and the rise of China (AU$284,000/ c.£177,740, 2014).

- The Lee Kong Chian distinguished research fellowship to fund stints at the National University of Singapore and Stanford University (US$26,000/ c.£17,600, 2015).

- A European Research Council award (with Michael Magcamit) to fund a postdoctoral fellowship on religion and conflict in Southeast Asia (€195,454/ c.£171,570, 2019).

- British Academy awards to fund research on Southeast Asia’s response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (£70,500, 2016) and my secondment to the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (£212,560, 2022).

Research students

I am always happy to consider supervising PhDs on topics connected to the work described above, or in the broad fields of:

- Marxist International Relations theory

- Gramscian state theory

- Southeast Asian politics, political economy, or international relations

- China’s international relations

- International sanctions

- Sovereignty and intervention

- Non-traditional security

- The New Cold War

Please contact me with a CV and a 1,500-word draft research proposal. For details of how to produce a proposal, research funding and other procedural matters please see the School of Politics and International Relations webpage.

Please note that I am not qualified to supervise theses on South Asia. Try my colleague Layli Uddin.